“There are ecologists in urban areas, and then there are urban ecologists”

– Dr. Chris Schell

This point made by my advisor (Dr. Christopher Schell) creates a clear distinction that there are urban ecologists who do not fully integrate social processes (nor the full human, e.g., perceptions, culture) in their studies. And there are urban ecologists who think of the city as a whole, incorporating all aspects of the landscape. As I dive into the field of urban ecology, I’m encountering this wall. How complex is it to really integrate more of the landscape into our scientific approach? And why wasn’t this a high priority for the field? This led me to read a handful of foundational papers in my field around the social-ecological framework.

Social-ecological thought isn’t exactly new to the field of urban ecology. However, it wasn’t until recently that urban ecology started explicitly discussing the parts of society that were integral in shaping concrete landscapes (see Schell et al. 2020 and Des Roches et al. 2020). But how did we get here? I’ll briefly talk about some foundational urban ecology papers to catch us up.

In 2000, “A New Urban Ecology” entered the scientific scene (Figure 1). It brought an explicit call to incorporate the human into ecological thought and clearly outlined that human communities are a part of ecosystems. In doing so, Collins and colleagues reframed the field of urban ecology into one that requires the integration of sociology and adjacent disciplines to produce more fruitful knowledge. In doing this, they revisit “the city” through previous literature and dissect how it has been conceptualized (e.g., how do we define urban?). They do this by reminding us that traditional ecology positioned itself as primarily studying “untouched”/”pristine” ecosystems, with humans (and cities) being viewed as this “perturbing force” and, in a way, becoming the antithesis to nature and ecosystems. A perspective that I must highlight as one steeped in colonialism and white supremacy. Throughout this piece, the authors are sitting with two perspectives: (1) ecological theory can stretch over human-dominated landscapes and is sufficient in cities, or (2) due to the intrinsic nature of humans, ecological theory for non-human-dominated landscapes cannot fully encompass the environment and variables present, and thus a new urban ecological theory is needed. Both have been done, with their point being that moving forward, urban ecology should take on an multidisciplinary approach to fully address the complexities of urban ecosystems. And yet, there are still explicit drivers missing here when considering the city as an ecosystem and the role humans play.

The papers following this sought to build a more robust and inclusive social-ecological thought that truly captured the cityscape. Redman et al. 2004 offered insight into how bridging multiple disciplines can create a framework that generates stronger, and more in-depth, questions about the landscape. They do this by reviewing previous efforts in long-term ecological research and expanding on topics by identifying questions that could be asked, interrogating scale use, and general concepts that are important when doing transdisciplinary work. For example, they explicitly identify several social science patterns/processes that may be important to consider in a particular study (e.g., economic growth, demography) while highlighting key ways we think about ecosystems. Collins and others added to this discussion in 2011 by integrating Press-Pulse Dynamics. Press dynamics are slower, ongoing processes in the environment, both social and biophysical (e.g., sea-level rise, global warming), while pulse dynamics are quicker, short events that can dramatically alter the ecosystem and its services (e.g., hurricanes, flash floods) and thus are harder to integrate into frameworks because of their unpredictability. Unlike previous social-ecological frameworks (e.g., Redman et al 2004), this paper integrates ecosystem services and how these services fluctuate/are impacted by human behavior.

So now we’re in 2011 and we (sort of) finally understand that humans are important players in urban ecosystems and shape a lot of ecological processes. But what about the temporality of the land? Ramalho & Hobbs (2012) address this by reviewing urbanization in ecology and emphasizing that current frameworks have misleading assumptions about the system. Here, they introduce that processes should explicitly highlight temporal perspectives and consider land-use legacies in relation to environmental change. This is particularly important as the world continues moving toward an urbanizing planet where landscapes are being urbanized on different time scales, both globally and locally. Thus, the impact of urbanization in one area of a city shouldn’t be equated to another area as it’s not uniform (Figure 2). When combined with other frameworks (such as Collins et al. 2011), this framework could produce incredible science.

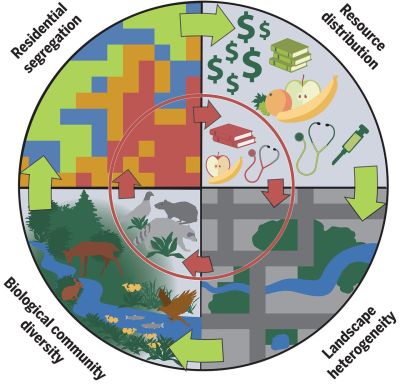

Jump ahead to 2016 and urban ecology is discussing what it means to produce science that is for the city. In McPhearson et al. (2016) (and Pickett et al. 2016), researchers are distinguishing what it means to do work that is “in the city”, “of the city” and “for the city”, leading to a discussion of a more holistic, integrated scientific framework. But somehow, we’ve still walked around a key player in human-dominated landscapes, especially cities. White supremacy and colonialism, which has undeniably shaped today’s world. Fast forward to 2020, Schell and colleagues address this by publishing a piece that eloquently ties ecological and evolutionary processes to systemic racism in cities, including the acts of redlining (more on redlining here) and segregation (see my summary of Schell et al 2020 here). This piece is then strongly complemented by Des Roches et al. (2020) outlining the socio-eco-evolutionary processes in cities and clearly illustrating the interdependency (and feedback loop) that is human existence and the environment (see my summary here).

So, where do we go now? What’s next for urban ecology? What will be the next game-changing perspective that unlocks more for our understanding of environmental processes in cities? For me, I see a more transdisciplinary urban ecology that stitches in post-colonial theory, environmental justice theory, political ecology, and queer theory. I see a field that begins disentangling how human attitudes and perceptions of landscapes, animals, and the environment (and how this may be tied to the Western concept of whiteness, environmental domination/extraction, gender projection, human exceptionalism, etc.) can shape wildlife biology and the landscapes they experience (and much more!). I briefly discuss a bit of this vision, with a focus on queer theory, in a post titled “What’s Missing in Urban Ecology?”.

What do you think is missing in urban ecology (or your field) that could unlock a new world of questions?

Featured Image is Adapted from Des Roches et al 2020 (citation below)

References:

Redman, Charles L., J. Morgan Grove, and Lauren H. Kuby. 2004. “Integrating Social Science into the Long-Term Ecological Research (LTER) Network: Social Dimensions of Ecological Change and Ecological Dimensions of Social Change.” Ecosystems 7 (2). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10021-003-0215-z.

- Social-Ecological Frameworks and What the Future May Hold - May 26, 2022

- What’s Missing in Urban Ecology? - May 10, 2022

- Urban Wildlife Spotlight: The Monk Parakeet - September 2, 2021

Leave a Reply